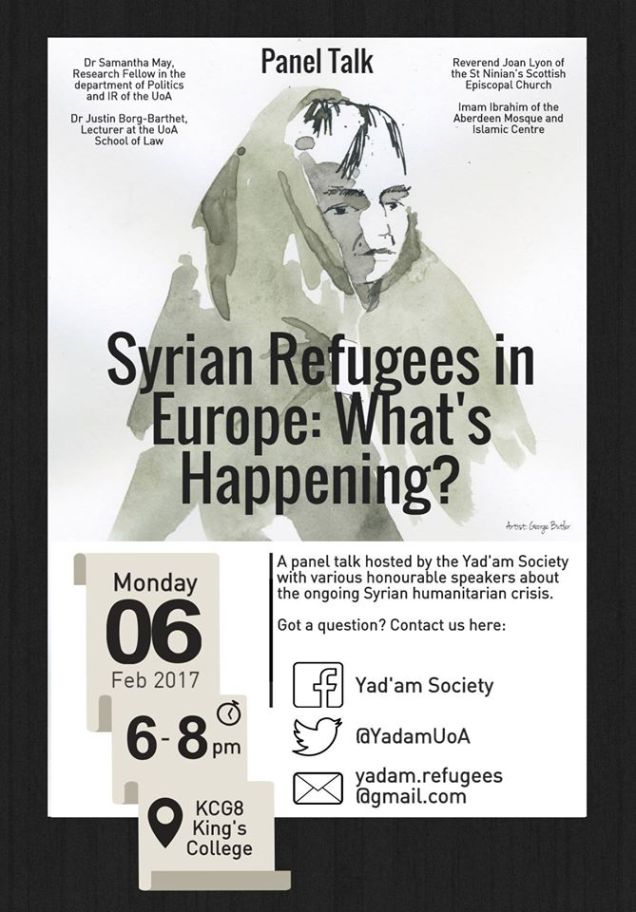

The following is the text of remarks made by our Dr Justin Borg-Barthet at a panel discussion organised by the Aberdeen University Yad’am Society on 6 February 2017.

Introductory remarks

To begin with, it is worth considering why we in Europe should be concerned about the Syrian refugee crisis. Syria, after all, is not a European state and Syrians do not traditionally consider Europe to be their most immediate cultural hinterland. It is arguable, therefore, that Syria and Syrian refugees are not European problems.

But let’s be clear that since the end of the Second World War, at least, we have all embraced the principle of a common humanity. This is not merely a political statement, but is a principle entrenched in international law – like the 1951 Refugee Convention – and in the human rights law of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In the spirit of a broader humanity, I will not confine my comments to matters solely pertaining to the Syrian crisis. That crisis is simply the most recent in a series of developments which have seen the European Union fall short of its humanitarian and human rights obligations in respect of refugees and asylum seekers. It illustrates, in stark terms, an ongoing systematic and systemic problem in the EU’s relations with its neighbourhood.

In these brief remarks, I will address two main points. First, I wish to highlight a failure to comply with obligations. Secondly, I will consider briefly the constitutional policy implications of this failure, and make modest recommendations about how the Union could seek to address persistent problems.

Humanitarian and human rights obligations

EU human rights law has come a long way since the first steps towards European integration in the 1950s. This is most clearly seen in recent judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) regarding relocation of asylum seekers. In the NS case, Afghan asylum seekers in the UK were to be returned to Greece, which was their point of entry into the EU. Under the Dublin Regulation, Greece was responsible for processing the asylum claim. It was found, however, that the applicants’ right to be free from inhuman and degrading treatment would be at risk due to systemic problems in Greece. It followed that the UK could not return the asylum seekers.

The decision of the CJEU is, of course, to be applauded. It demonstrated a shift in emphasis from the rights of states to those of individuals. However, that judgment did nothing to alter the facts on the ground for most asylum seekers in Europe.

Reception conditions

Greece, Italy and Malta are the main ports of entry for refugees and asylum seekers from Africa, the Middle East and further afield. Each of those states has been found to be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights due to their inadequate treatment of refugees (e.g. M S S v Belgium and Greece (2011) 53 EHRR 2; Aden Ahmed v Malta ECHR App No 55352/12 (23 July 2013); Hirsi Jamaa v Italy (2012) 55 EHRR 21). In particular, reception conditions have been found to breach the prohibition of the right to liberty (due to forced detention) and, consequently, the prohibition of torture (due to the adverse effects of detention on mental health).

The problems in these three states are compounded by the fact that they bear the brunt of responsibility for dealing with migration to the EU. Whatever lofty declarations are made in the north and west of Europe, and despite images of hundreds of people trekking across a continent, the fact remains that pressures are concentrated in a small number of member states, which brings us to another problem of so-called burden sharing.

Burden sharing

A number of EU member states have long argued that there should be a system of compulsory burden sharing. In other words, the responsibility for hosting and processing asylum seekers should be shared between the Member States rather than being concentrated in border-states. The Geneva Convention arguably requires burden sharing as a matter of international law. EU law itself is founded on the principle of solidarity between states and people.

But still, wealthier states which are geographically insulated from the crisis have resisted compulsory burden sharing. Instead, they initially accepted a voluntary system. Latterly, a system of agreed relocation has been put into place, but the Member States have been very slow in taking any practical steps to ensure that pressures are distributed.

This is important to member states which face significant financial and social burdens. And because of those burdens, it is also important to asylum seekers. No member state is able single-handedly to accommodate and welcome the numbers that have been crossing the Mediterranean Sea. In the absence of collective action, asylum seekers remain vulnerable to the inadequacies of ill-equipped states.

Relocation to third countries

Following repeated failures in seeking compulsory burden-sharing within Europe, southern EU member states have changed their strategies. Rather than advocating relocation of asylum claimants within the EU, they have successfully argued for the externalisation of problems through so-called reception centres in Turkey and Libya. An agreement with Turkey is now fully operative.

Of course, there is nothing wrong, in principle, with supporting Turkey in its own efforts to provide reception to migrants, or in discouraging dangerous sea-crossings. But the fact is that, for all the failures of EU member states, the treatment of asylum seekers in Turkey and Libya leaves far more to be desired.

You may recall that I mentioned the judgment in NS earlier. In that case, it was decided that Member States could not return migrants to other EU States if there were systemic problems in the destination state.

There is no logical reason why that principle should not be applied between the EU and third countries in the same manner as it is applied within the EU. Fundamental rights, after all, bind the member states whether they are acting unilaterally or collectively. The principle of non-return in the judgment in NS should preclude the return of asylum seekers to Turkey. Yet, just last week, the informal council meeting in Malta concluded that the Turkey agreement should be replicated in Libya. Far from questioning the strategy, the Member States are seeking instead to entrench and extend it to ever more questionable destinations.

Tellingly, humanitarian corridors were not addressed in the council conclusions, but were determined to be a matter for the future. We will deal with that once we have secured the border. Now where have we heard that before?

Constitutional observations

The refugee and migrant crises expose cracks in the institutional architecture of the European Union. There has been a consistent failure to act according to constitutional principles due to the stranglehold that the member states hold over law and policy-making processes. If they refuse to act, the Union’s principles are meaningless in practice. While the EU rightly baulks at President Trump, its own record of treatment of refugees has not been pristine.

Of course, it is difficult for the Union and Member States to act when public opinion is unsupportive. But let’s not forget that public opinion is divided. It is far from unanimous in its opposition to migration.

And there is equally a great danger in failing to uphold and defend principles. If constitutional principles are not upheld, this lends an air of legitimacy to the ideologies that are threatening the EU’s collective model itself. By reducing the stranglehold of states, and focusing instead on representation of people and rights of people, the Union could ensure that collective action remains possible, and that it is given further effect in future.

In other words, far from the answer being less Europe; far from the answer being the dismantling of Schengen; and far from the answer being border fences between states; the answer is a more principled Europe – a more meaningful European Union that is capable of acting internationally in accordance with its founding principles.

Dr Borg-Barthet is the co-author (with Carole Lyons) of an analysis article in the 2016 Edinburgh Law Review. ‘The European Union Migration Crisis’ is currently the ‘Most Read’ article online.